Malnourished Emperor Penguin Begins Recovery After Epic 2,000-Mile Journey to Australia

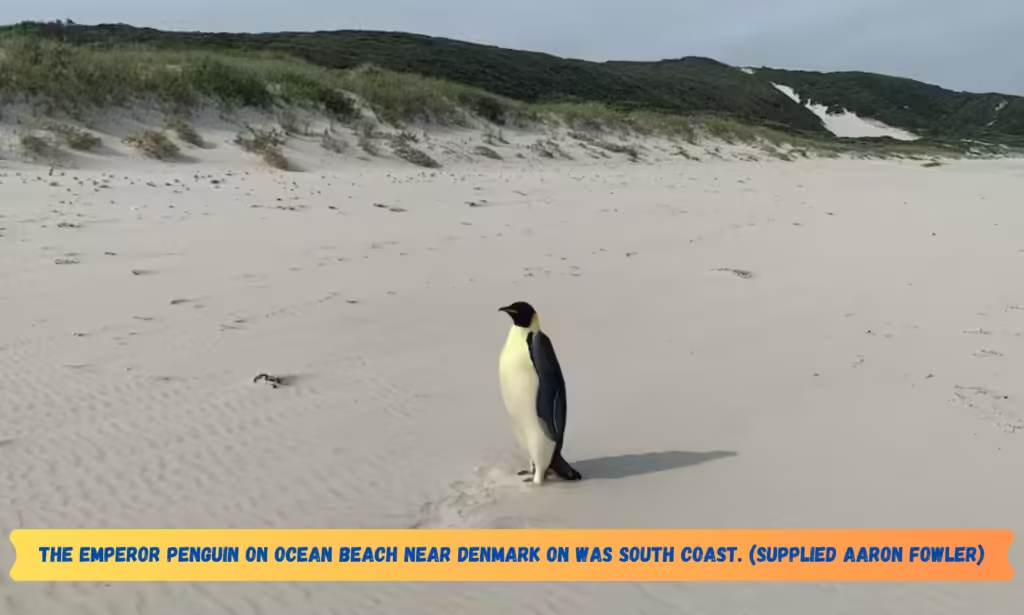

An emperor penguin, affectionately named Gus, is currently undergoing a rehabilitation process after an extraordinary and arduous journey that saw him swim over 2,000 miles from Antarctica to the southern coast of Australia. Gus’s incredible journey, which began in the frigid waters of Antarctica, ultimately led him to a tourist beach in the southwest region of Australia, where he was discovered by local surfers on November 1, 2024.

According to an official statement from the Australian government, the penguin’s unexpected arrival on the shores of Australia has captured the attention of wildlife experts and conservationists alike. This lone penguin, who is believed to have made the perilous swim across the Southern Ocean, was first spotted by Aaron Fowler, a local surfer.

Initially, Fowler and his companions assumed the bird might be another species of seabird. However, they quickly realized something was unusual when the bird began to approach the shore. Fowler recalled the moment, explaining, “We had a look at what was going on, and there was this large bird in the water. We thought it was just another sea bird at first, but then it kept coming closer and closer — it was way too large. Then it simply got up and walked straight toward us.

Upon further inspection, it was clear that Gus, the emperor penguin, was in poor condition. Weighing only 51 pounds (about 23 kilograms), Gus was far lighter than the typical weight range of a healthy emperor penguin, which normally weighs between 55 and 100 pounds (25 to 45 kilograms). This dramatic weight loss suggests that Gus may have been struggling with malnutrition and exhaustion after his long and challenging journey.

Since his discovery, Gus has been taken into care by a team of local wildlife experts from the Department of Biodiversity, Conservation and Attractions in Western Australia. His health is being restored by them. As part of his rehabilitation, Gus is regularly sprayed with cool mist to help him cope with the much warmer climate he now finds himself in. Emperor penguins are typically accustomed to the freezing temperatures of Antarctica, so adjusting to the heat of an Australian summer has been an added challenge for the already weakened bird.

The penguin’s recovery is a complex process, and officials are working to ensure that Gus is in the best possible condition before making any decisions about his future. At this stage, it is unclear whether the penguin will be returned to his native habitat in Antarctica after he recovers, or whether other options will be considered. As the recovery process unfolds, the team at the Department of Biodiversity continues to explore all possible avenues for his well-being.

This event is also a reminder of the broader environmental challenges faced by emperor penguins and other species that rely on the Antarctic ecosystem. According to the Center for Biological Diversity, a nonprofit organization dedicated to protecting endangered species, emperor penguins are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. The ongoing melting of ice shelves in Antarctica threatens their natural habitat, while rising global temperatures and ocean acidification create additional challenges for the penguins’ survival. Scientists have projected that without significant reductions in carbon emissions, up to 80% of the world’s emperor penguin population could disappear by the end of this century.

Furthermore, the penguins’ access to food is increasingly threatened by industrial fisheries, which compete with the birds for key prey species, exacerbating their struggles. As such, Gus’s unexpected appearance on an Australian beach serves as a stark reminder of the urgent need for comprehensive conservation efforts to address the multiple threats facing emperor penguins and other marine life.

For now, Gus remains in the care of wildlife experts, and efforts continue to help him regain his strength and health. His remarkable journey across the Southern Ocean has drawn international attention, and many are hopeful that he will recover fully, even as the broader implications of his story highlight the fragile state of polar ecosystems in the face of climate change.

Emperor Penguin: Aptenodytes forsteri – A Deep Dive into the Largest Penguin Species

The Emperor Penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri) holds the title of the largest member of the penguin family (Spheniscidae), a title it wears proudly, standing out not only due to its size but also for its distinct physical appearance, behavior, and survival strategies. With its majestic black-and-white plumage and vibrant orange-yellow markings, this incredible bird has captured the fascination of scientists and wildlife enthusiasts alike. Indigenous to the harsh, icy conditions of Antarctica, the emperor penguin is a symbol of endurance and resilience, thriving in one of the most extreme environments on Earth.

In this article, we will explore the Emperor Penguin’s physical characteristics, behavior, feeding habits, reproductive processes, and the increasing threats posed by climate change. We will also examine the bird’s life cycle, its struggle for survival, and the ongoing conservation efforts to protect this remarkable species from potential extinction.

Physical Characteristics of the Emperor Penguin

The emperor penguin’s physical attributes are as unique as its lifestyle. Its distinct black-and-white coloration is coupled with striking orange and yellow markings on the head, neck, and chest, making it one of the most visually captivating birds in the world. The stark contrast between its black back and white belly is not merely for aesthetic purposes; it plays a role in regulating the bird’s body temperature, helping it survive in the extremely cold temperatures of Antarctica.

Size and Dimensions

The largest penguin species is the emperor penguin. Adults can grow up to 130 cm (50 inches) in length and can weigh between 25 to 45 kg (55 to 100 pounds). Males and females are of similar size, although there can be slight variations based on individual health and environmental conditions. This size makes them particularly well-equipped for the cold Antarctic conditions where they reside, offering them the size and mass needed to retain body heat and withstand the extreme weather.

Juvenile emperor penguins, or chicks, are considerably smaller than adults, with their weight reaching a fraction of that of a grown penguin. Their plumage, when they first hatch, is a soft, silver-gray down, which helps insulate their bodies. As they grow, their feathers change, becoming more similar to the adults, with pale gray feathers replacing the rich orange and yellow hues found in mature penguins.

Distinctive Features

- Feathers and Coloring: Adult emperor penguins have a smooth, sleek layer of feathers, providing both insulation and waterproofing. Their heads are characterized by black feathers, except around their eyes, which are encircled by white feathers that provide a striking contrast against their dark plumage.

- Physical Adaptations: Their large size and dense feather layers provide them with the thermal insulation needed to survive in one of the coldest places on Earth. In addition, their wings, which are adapted for swimming rather than flying, make them exceptional divers, propelling them through water with remarkable speed.

Comparison with the King Penguin

The emperor penguin closely resembles the king penguin (Aptenodytes patagonicus), a smaller species found on sub-Antarctic islands. While both species share similar physical features and behaviors, the emperor penguin is notably larger, with the king penguin averaging about 90 cm (35 inches) in length. Despite their similarities, the emperor penguin is the undisputed giant of the penguin world, and its larger size helps it endure the particularly harsh conditions found in Antarctica.

Feeding Habits and Diet of the Emperor Penguin

One of the most fascinating aspects of the emperor penguin is its ability to dive to extraordinary depths in search of food. These penguins are superb swimmers, capable of diving to depths of approximately 550 meters (1,800 feet), making them the world’s deepest-diving birds. Their diving skills are essential for hunting in the frigid waters surrounding Antarctica, where they capture their prey.

Diet and Prey

The emperor penguin primarily feeds on a diet of krill, fish, and squid. These species are abundant in the waters near the Antarctic ice shelves, and the penguins are adept at hunting them. The penguin dives beneath the ice to capture these prey species, and their remarkable endurance allows them to remain submerged for up to 22 minutes at a time.

Emperor penguins also display impressive migratory behaviors in their search for food. Some individuals have been recorded swimming hundreds of miles in search of prey, reaching areas such as the South Shetland Islands, Tierra del Fuego, and even New Zealand. This migration is not just for survival—it is a testament to the penguin’s endurance and adaptability in seeking food across a vast and often challenging environment.

Predators

While they are expert hunters, emperor penguins also face several natural predators. Killer whales (Orcinus orca) and leopard seals (Hydrurga leptonyx) are among the primary predators of adult emperor penguins, preying on the birds when they venture too close to the surface. Giant fulmars (Macronectes giganteus), large seabirds, also pose a threat to both eggs and young chicks, often preying on the vulnerable offspring in the early stages of development.

These predators add to the immense challenges that emperor penguins face in their harsh environment, where they must constantly evade danger while maintaining the energy required for survival.

Reproduction and Breeding Behavior of the Emperor Penguin

Emperor penguins are known for their elaborate and highly specialized breeding behaviors. Their breeding cycle is uniquely adapted to the Antarctic environment, with timing and temperature control playing critical roles in the survival of their offspring.

Mating and Courtship

Emperor penguins are serially monogamous, meaning that they typically form a bond with a single mate during the breeding season, although they may choose a new mate each year. Courtship begins in late March to early April, after both males and females have returned from their ocean foraging expeditions. Once paired, the couple will engage in a series of displays and behaviors that help strengthen their bond.

Egg Laying and Incubation

In late May or early June, right before the Antarctic winter arrives, the female emperor penguin lays a single egg. The timing of the egg-laying process is critical, as the long incubation period must align with the arrival of summer when the chances of survival for the chicks are higher.

After the female lays the egg, she transfers it to the male, who assumes the responsibility of incubating it. For the next 60-68 days, the male will incubate the egg in a brood pouch located on his abdomen. During this time, the female will leave the colony to forage for food, embarking on a journey that can cover 80 to 160 kilometers (50 to 100 miles). The male does not eat during the incubation period, relying solely on his fat reserves to sustain him.

This period of incubation is extremely challenging, as the male must endure gale-force winds, freezing temperatures that can drop to –50 °C (–58 °F), and periods of darkness. The penguin huddles with others for warmth, often gathering together in “huddles”—a behavior designed to conserve body heat and protect against the elements.

Hatching and Chick Rearing

When the chicks finally hatch in August, they are weak and vulnerable. The female returns to the colony to relieve the male of his incubation duties, and both parents work together to care for the chick. The male continues to feed the chick a milky substance produced in his esophagus, which is regurgitated into the chick’s mouth.

As the chick grows stronger, it will stand on the feet of one of its parents to stay warm, protected from the harsh environment. However, the cold is not the only danger the chicks face. “Unemployed” adults—those who have lost eggs or chicks—often become a threat to the surviving offspring, sometimes interfering with the care of chicks or even causing increased mortality.

Life Cycle and Juvenile Development

The journey from hatchling to maturity is long and fraught with challenges. During the crèche stage, the chicks gather in groups, known as creches, to protect each other from the cold and predators. Their soft, downy feathers gradually shed, replaced by a coat of stiff, adult-like feathers. By December or January, the juveniles are fully fledged and are ready to leave the colony to venture out into the sea to begin their lives as independent foragers.

Juvenile emperor penguins will return to the breeding colony for the first time at the age of five, ready to mate and begin the cycle anew. While they typically live 15 to 20 years in the wild, some emperor penguins can reach 40 years of age in captivity, where conditions are controlled and threats are minimized.

FOR MORE CLICK bb